The six cello suites were written between 17, when Bach was employed as Kapellmeister to the music-loving Prince Leopold von Anhalt-Köthen. While the pitches corresponding to the name Sacher may be the point of departure for this work, Dutilleux’s real ‘subject’ in these three movements is the resonance of the cello itself, and the range of possible ways for summoning it up and manipulating it. This musical cryptogram also inspires the Vivace last movement, but it is buried in the intervals of the whirling pattern of triplet 16ths of the opening and in various transpositions and transformations of these pitches throughout. The second movement, marked Andante sostenuto, explores the rich low register of the cello, but for most of its duration only hints obliquely at the intervals making up the musical spelling of Sacher’s name, which is revealed in six bold strokes just before the end. (The cello’s normal range extends down only to low C, but for this work Dutilleux has the instrument tuned down to low B flat.) Near the end of this movement he introduces a short quotation in quivering 32nd-note double-stop tremolo from Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, yet another work commissioned by Sacher.

He also likes to ‘anchor’ his musical gestures around stable recurring pitches, from which his gestures depart and to which they constantly return, as is the case in this movement with the augmented 5th B flat – F# at the bottom of the cello’s pitch range.

DUTILLEUX STROPHES SERIES

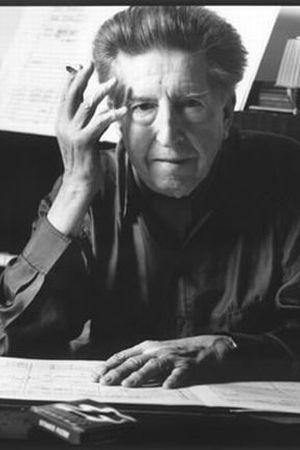

First we hear E flat, then E flat-A, then E flat-A-C-B natural, and then finally the entire series of pitches making up the ‘musical spelling’ of the name Sacher. In his works Dutilleux had a tendency not to introduce his thematic material in complete form right away but rather to slowly unveil it, as he does at the opening of the first movement of his Trois strophes. The spelled out musical motive to be used was therefore: E flat-A-C-B flat-E-D. In 1976 Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich set about to celebrate Sacher’s 70th birthday by commissioning new works for solo cello from 12 of the Western world’s leading composers: Conrad Beck, Luciano Berio, Pierre Boulez, Benjamin Britten, Wolfgang Fortner, Alberto Ginastera, Cristóbal Halffter, Hans Werner Henze, Heinz Holliger, Klaus Huber, Witold Lutosławski … and Henri Dutilleux.Įach piece was to use the dedicatee’s name spelled out ‘musically’, i.e., with each letter representing a musical pitch – Es being the German notation of E flat, H being B natural and R ( re in the language of solfège) as D. These commissioned works include Stravinsky’s Concerto in D for string orchestra, Bartók’s Divertimento for Strings, and Richard Strauss’ Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings. With a family fortune based on a controlling share of the Hoffman-LaRoche pharmaceutical empire, he commissioned works from some of the century’s greatest composers. Swiss conductor Paul Sacher (1906-1999), founder of the Basel Chamber Orchestra, was an immensely important figure in 20th-century music.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)